Figures of the Fool

From the Middle Ages to the Romantics

Studied by social and cultural history, the fascinating figure of the madman, who was part of the visual culture of men in the Middle Ages, has rarely been studied from the point of view of art history: yet between the 13th and the middle of the 16th century, the notion of madness inspired and stimulated artistic creation, both in the field of literature and in that of the visual arts.

For the general public, medieval art is essentially religious. However, it was the Middle Ages that gave substance to the subversive figure of the madman. While it has its roots in religious thought, it flourished in the secular world to become an essential element of urban social life by the end of the period.

For medieval man, the definition of the madman is given by the Scriptures, in particular the first verse of Psalm 52: “Dixit insipiens…” (The fool has said in his heart: “There is no God!”). Madness is above all ignorance and absence of love for God. Conversely, there are also “madmen of God”, such as Saint Francis. In the 13th century, the notion is therefore inextricably linked to love and its measure or excess, first in the spiritual domain, then in the earthly domain.

The theme of the madness of love haunts chivalric romances (that of Yvain, Perceval, Lancelot or Tristan) and their numerous representations, notably in illuminations and ivories. Soon, the character of the fool interferes between the lover and his lady: he is the one who denounces courtly values and emphasizes the lewd, even obscene, character of human love.

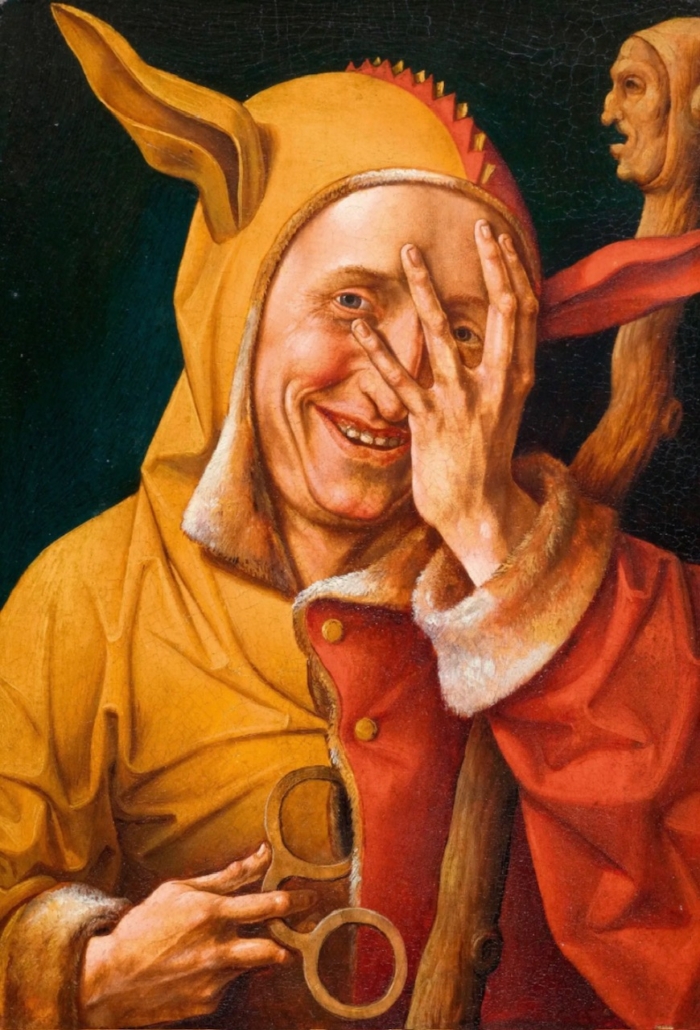

From mystical or symbolic that he was, the fool becomes “politicized” and “socialized”: in the 14th century, the court fool becomes the institutionalized antithesis of royal wisdom and his ironic or critical speech is accepted. A new iconography is established and the fool is recognized by his attributes: hobby horse, striped or half-striped coat, hood, bells.

The 15th century is that of the formidable expansion of the figure of the fool, linked to carnival festivals and folklore. Associated with social criticism, the fool serves as a vehicle for the most subversive ideas. He also plays a role in the torments of the Reformation: in this context, the fool is the other (Catholic or Protestant). At the turn of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, his figure has become omnipresent, as shown by the art of Bosch and then that of Bruegel.

In the modern era, the figure of the institutional fool seems to be gradually fading, replaced in the courts of Europe by the jester or the dwarf. From the middle of the Age of Enlightenment, madness takes its revenge to appear in other, less controlled forms. The exhibition concludes with an evocation of the 19th century’s view of the Middle Ages through the prism of the theme of madness, but with the tragic, even cruel, light that political and artistic revolutions gave it.